Inannak: Genesis

Published: 2022-12-22

Categories: Inannak, Maps, Worldbuilding

Series: Inannak

Previous: Inannak: the Website

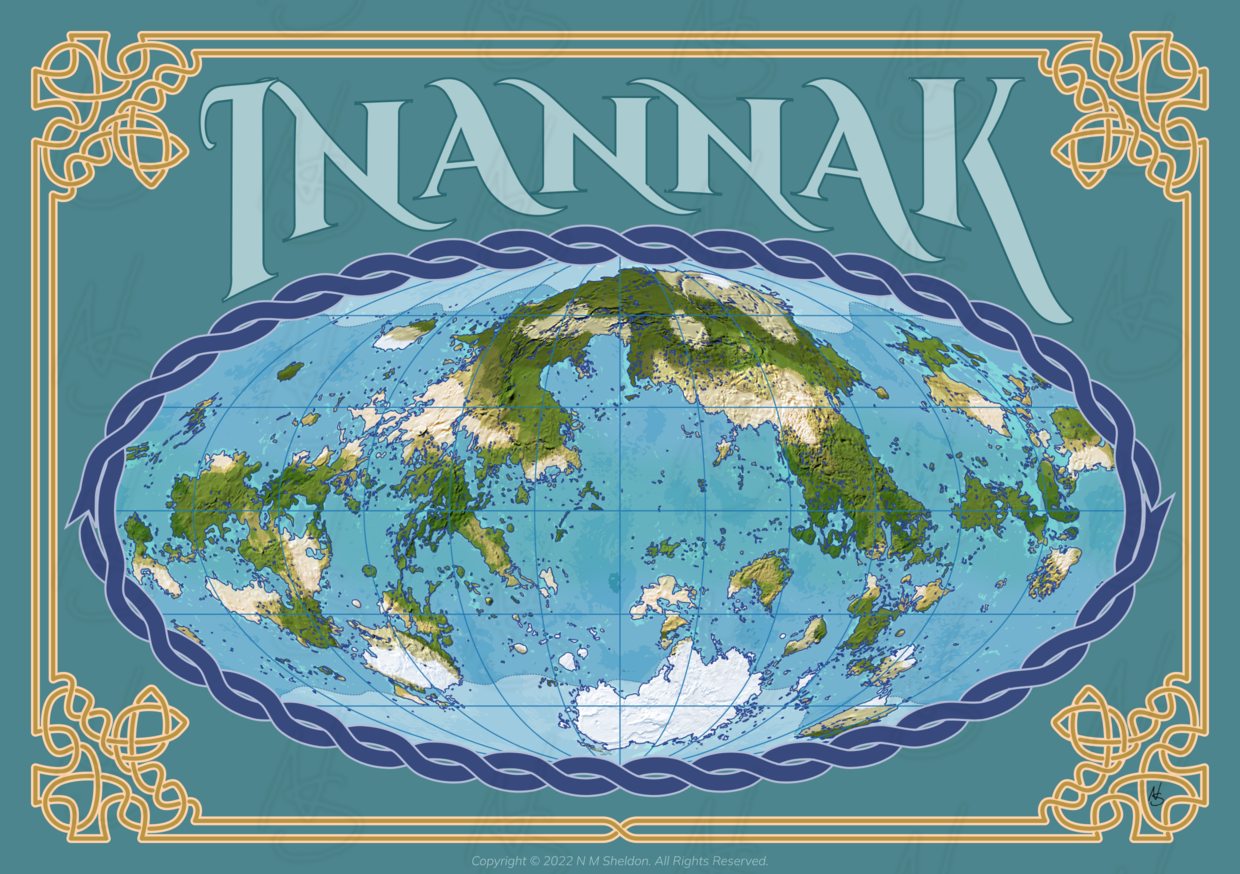

I’d like to present to you a world map for my Inannak project. I call this a preview, I may get to a full poster map at some point. With this image, I’m also playing with decorations, text art, and other gewgaws, which may be important in fantasy maps. I appreciate any comments, suggestions, or questions.

But the gewgaws took only a few days, the real work was the map itself. That’s what I want to talk about today. This map represents a fully developed physical world, with landforms, water features, climate, and vegetation growing on it.

I won’t go into the technical details of how I did this. But for the sake of the hobby, I will provide a summary.

A Verisimilar World

There is no single process for building a fantasy world. While there are natural orders to some pieces (climate before weather, languages before lore, etc.), the process depends on what you’re building and who you are. In this case, I’m starting with a physical map of the world because that’s what I wanted to do.

My vision for Inannak is what I will call a verisimilar fantasy world – a world with the appearance of reality. While Inannak is a fantasy world, it has geography that seems to be true. It has working natural systems, even if those systems are based on fantasy physics. For such a world, everything connects. For example, the climate of the local village where the story starts out depends on whether it is in its latitude, prevailing winds, and proximity to mountains and coast, which depends on a global placement of continents.

This necessitates a global-down approach. In some world building, you start with that local village, then add the wilderness to adventure in when the story requires. You don’t discover the other continent until the tenth book. In a global-down approach, I need to start with that other continent and work towards the local. I need to know what the whole world looks like before I can describe the village.

To make Inannak verisimilar, I used a technology I’m familiar with called geographic information systems (GIS). That is a pretentious phrase for computerized maps. GIS allows me to use computer processes to solve certain geographic problems required to achieve versimilitude, based on our knowledge of Earth. This is much simpler than trying to figure these things out by hand.

In The Beginning

I started with some important facts about Inannak. These are decisions I need to make that will have an effect on my process.

Inannak is a spherical world. This would be (almost) a given in a science fiction universe, but in a fantasy world it should be far from given. I’ve seen a lot of fantasy worlds that are planets in a solar system that have some magic on them. That’s fine for them, but there is much more room to move around in. I submit for your consideration Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, and the four elemental worlds of Margaret Weis’s and Tracy Hickman’s Deathgate Cycle.

Fantasy worlds have more leeway, because few people will look deep into their physics. And if they do, you can say that there’s some magic that counteracts the problems. To paraphrase Arthur C. Clarke, any sufficiently different laws of physics in another universe are indistinguishable from magic in ours.

I’m not going as far as a flat world sitting on the back of elephants. I’m starting with spherical data as a basis, so that won’t work. But even so, Inannak is not in a real world space. It is a geocentric (or inannak-ocentric) universe with a system of astronomical bodies fixed in crystal spheres that orbit the world.

The crystal sphere which contains the sun orbits Inannak in 360 days. But Inannak itself also rotates daily on a tilted axis, allowing for day/night, weather and seasons similar in nature to Earth’s.

On the inside, Inannak does not have a magma core, nor continental plates. There are no mid-ocean ridges and subduction zones. Instead, the land is shaped by the whims of elemental society and politics. Elemental spirits of stone create mountains like a child at a beach. Volcanoes may be the sites of warfare between those and the spirits of fire. And all this build-up may be brought down by attacks against both from violent wind and water spirits.

More details of the world will be in the book.

Construction

I divided the genesis of Inannak into three phases. First, I needed data to start with. Then I needed to create the water features. Third, I needed to create a climate for the world to determine what the regional environments are like.

For much of this work, I used a program called QGIS, along with several related extensions and tools.

The Data

To create a world like this, I needed elevation data: the basic structure of the surface of the world. This is usually not an easy task. I’ve been searching for nice ways to build this for years. Freeform manual land building doesn’t cut it. Individual biases and bad estimations break down the verisimilitude.

So far, I’ve found a lot of random terrain generation algorithms, but nothing comes anywhere near natural tectonic processes. If you are ever interested in creating a world from scratch, I’d suggest perusing the Worldbuilding Pasta blog, specifically what the author has to say about simulating plate tectonics.

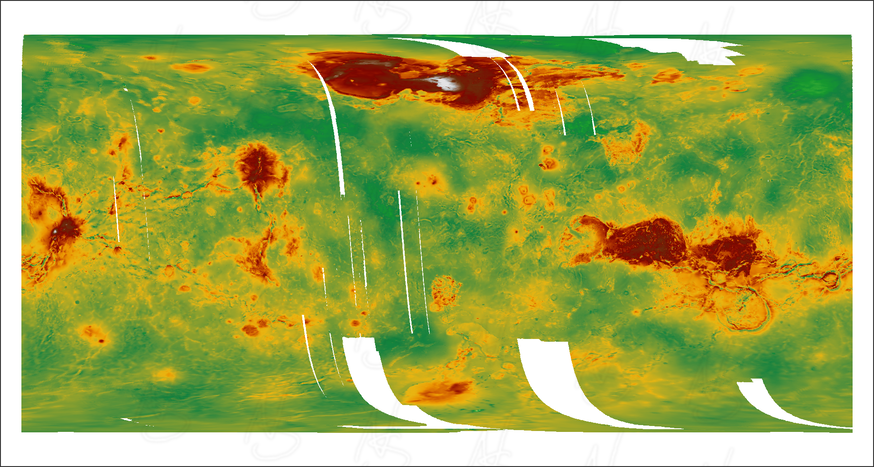

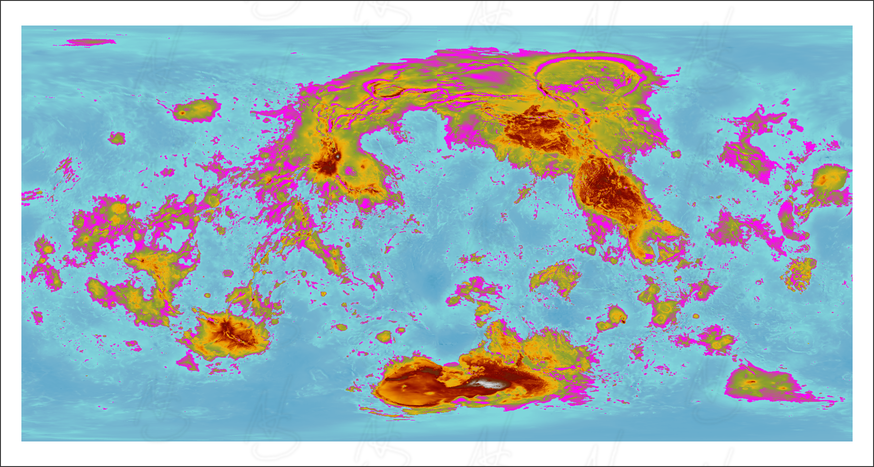

Those failed searches for easy terrain led me to the idea of using something from the real world. Unfortunately, anything I use off of Earth will be too recognizable, which isn’t what I wanted. Thus, I was delighted when I found out there was data available for non-Earth planets. I chose Venus for the extent of the data available, and for how few obvious craters there were.

I downloaded the “Venus Magellan Global Topography 4641m v2” data from the US Geological Survey. Below is an image of what I pulled into QGIS, with coloring added for elevation:

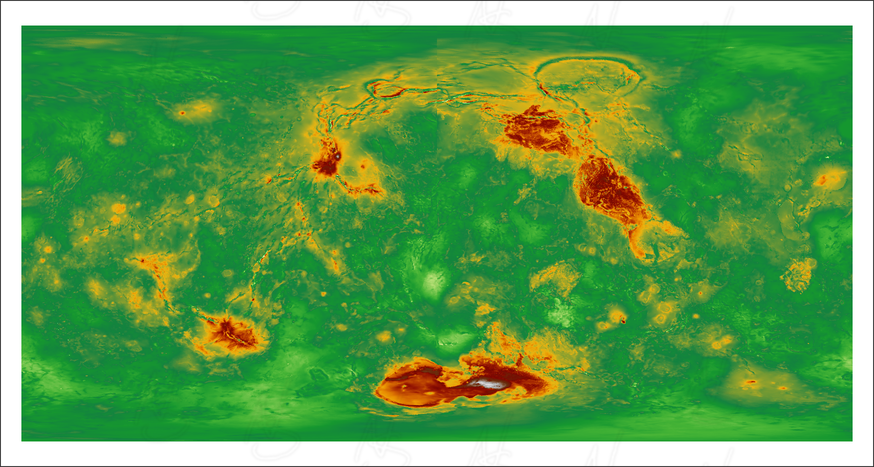

As you can see, it required processing to get the data to where I wanted it, but it was easier than running the plate tectonics by hand. At most, I needed to fill in the empty spots, which I did with a combination of random data and interpolation. But I also wanted to adjust the world’s axis to create a more interesting combination of continents. All of that led to this:

I guess it kind of looks like some sort of sea creature.

Water Features

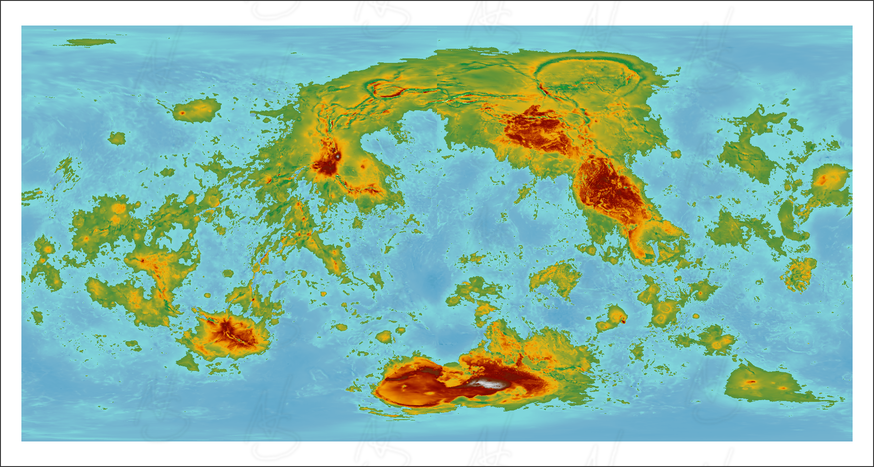

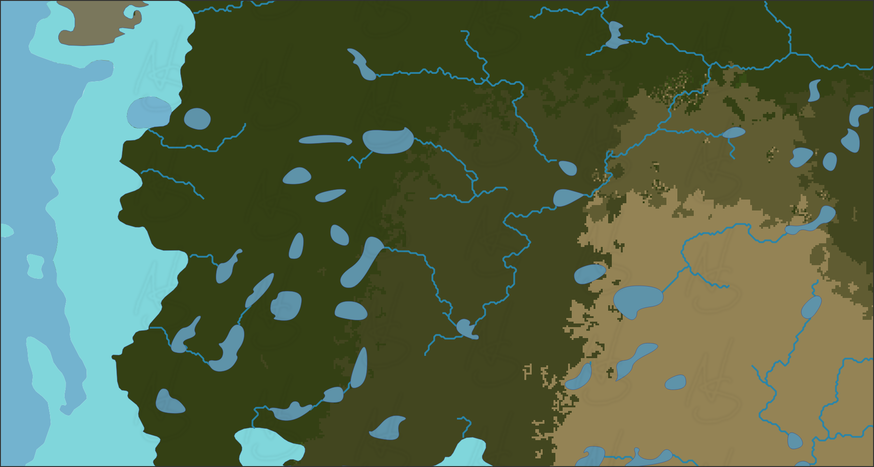

While I could manually draw ocean, lakes, and rivers over this map, there’s no reason to do this. By basic physics, water flows to the bottom. Since I have an elevation map, it’s not difficult to compute where that flow occurs. I chose a sea level based on an expected percentage of land covered with ocean:

Attempting to fill in the ocean based on that sea level led me to my first discovery. Inannak, probably because Venus doesn’t have Earth-like orogeny and erosion cycles, is full of closed basins. These are areas of land which, due to topography, do not have any water flowing to the ocean. On Earth, we have a few examples: the Great Basin in the western part of the U.S. is one I’m most familiar with. On Inannak, they’re all over the place. The below map shows these basins in ugly purple.

In fact, many of the basins on Inannak are deeper than the elevation I chose for the ocean. This means a lot of quite large Death Valleys, but hopefully not so deadly.

These basins led to another quirk of Inannak when I ran processes to determine where rivers and lakes should be. On Earth, most rivers eventually end in the ocean. That’s actually much less common on Inannak, which may lead to many salty lakes. It’s also possible that on a fantasy world with extensive underground terrain, many of these are not endorheic, but cryptorheic: the water might flow to the ocean through massive underground rivers.

You can see a couple of examples of this in the top middle of the map below:

I blamed this unique feature on the elemental land building processes, and moved on. Fantasy worlds should always have fantastic features.

Climates

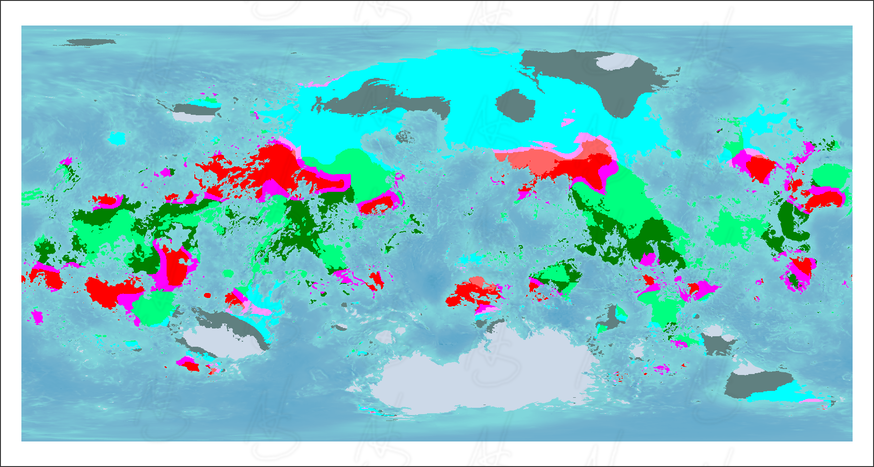

Climates were the part I was both dreading and anticipating the most. I’ve seen many tutorials and “cookbooks” explaining how to build realistic climates by hand. Those tutorials are vague and depend on extensive research into systems that are too complex to understand without heavy calculus. Many assume you’re drawing a traditional fantasy continent with triangles for mountains, where precision isn’t necessary. As far as I knew, software solutions were inaccessible to the casual user who isn’t a student of meteorology or climatology.

After several weeks of starting and restarting the climate with different techniques, I discovered the blog I mentioned above. The first article I read was the most thorough tutorial on climate design that I’ve seen. But, even better, it led me to a tutorial on getting an actual climate simulator to work on my little laptop.

As specified in that article, I used a tool called ExoPlaSim to generate climates for Inannak, plus some scripts and advice posted in the blog. It took a few days to configure, and about 12 hours to run. It still isn’t perfect, most of its failures I blame on the weakness of my laptop’s processor. But it was far better than trying to do it all by hand, and at least the results were systematic.

Here’s a map with the major climate zones, I didn’t give it a legend, they mostly run equator to pole in this order: Tropical, Steppe/Desert (in reds and pinks), Subtropical, Continental, and Polar (in grey and white).

From that, I did a little post-processing to make the climate edges more wiggly. I applied a natural color scheme found in the scripts provided in the Worldbuilding Pasta blog. And I added some hillshading for elevation:

The rest was just mapmaking.

How to Build a World

When I started on this phase, I had grand plans to give you routine updates and technical details of the process. It would have been enough for you to follow along, even recreate what I was doing.

But I kept putting that off. I told myself to wait until after I finished the rivers, the lakes, or the climate. But something deep inside I knew better. The extent of what I was putting together was too long for a simple blog post, or even a series.

This means you will not see a recipe for worldbuilding here on this blog. If there’s enough interest for that, I might reconsider and publish my notes as a supplement to the book.

What’s Next

The data for this map took a little longer than I expected, so I built the preview map above instead of something bigger. I will someday want a nice poster map, and I will also need some regional maps for the book. For those, I will have to interpolate some to the larger scales. I may also want to give it a more fantasy-style appearance, with hand-drawn mountains.

But more important, I need labels showing the names of places. And to get names, I’ll need two things: history and language. The latter is the next step in the building of Inannak, as I’ll need that for the history too, although both are interconnected.

Before I can do that, I have other projects to work on as well. I may need to take a break from Inannak for a time, so I can finish some other exciting projects.

So, this is what you get for now. See you soon and Happy Holidays.